|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

||

Contents |

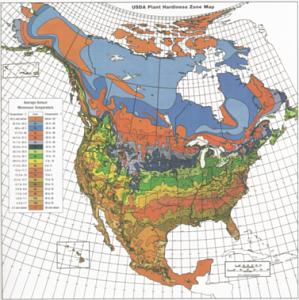

Plant Hardiness InformationUSDA Zone Map

Click map to enlarge. It is truly difficult trying to assign a hardiness zone to all plants, especially when using the minimal 10 USDA Zones. This is why we find it critical to differentiate between the "a" and "b" zones whenever possible.... we would prefer a "c" and "d" also. If no information exists, our computer randomly assigns numbers between 2 and 10 (we figure nothing worth having grows in Zone 1). Actually, too many nurseries unfortunately simply use the standard rule of nursery hardiness. If you don't know the zones, it becomes hardy from Zone 4-9 by default. A drawback to growing new and different plants is that there is no information on their hardiness. In some cases, we have been particularly conservative, possibly up to two zones too warm... if you are brave and like to try plants out of zone, we would love to hear your results. Let us know if your results were achieved with or without snow cover. Our hardiness zone information (both cold and heat) is the result of trials by us and other plant collectors around the country. Our zone information is based on information in the East and Midwest regions of the United States and has no significant relation to foreign countries like California, which has its own zone map. The USDA Hardiness Zone map is based on average winter low temperatures, and doesn't take into account rare extremes. While the map is based on a tremendous amount of data, it isn't perfect. Cold temperatures are only one factor that affect plant hardiness. After several years of mild winters, regions may exhibit "zone creep," where plants seem to be fine that are not truly suited to even "normal" winters. Cold temperatures for one night are not the same as cold temperatures for a period of weeks, even though the same low temperature is reached in both cases. In many cases, a low temperature of zero degrees may cause cellular damage that will start to heal if the temperature rises rapidly. If the temperatures remain low for several days, cell damage may continue, and result in the death of the plant. In areas with lots of snow cover, plants may survive normally deadly winter temperatures, due to the insulating effect of the snow. Layers of ice, however, are different, as they tend to keep oxygen from reaching the soil and can result in the death of many typically hardy plants. In areas with warm autumn nights, plants may die from a sudden freeze. This death does not occur from the actual temperatures, but instead from the plant not being acclimated to the cold weather. Plants in cooler zones that hardened off earlier would survive much lower temperatures. Another overlooked, but very important factor, is winter moisture. While many plants, especially Southwest natives, can survive incredibly low temperatures, they cannot tolerate rain in the winter dormant season, especially when temperatures drop into the teens and below. Another phenomenon, seen in England and in the cool areas of the West Coast of the US is the difference in winter hardiness due to a lack of summer heat. In many plants native to warmer climates, summer heat causes increased sugar production, which allows the plants to survive more stress in the winter. In areas without summer heat, a particular plant may only be hardy to 20 degrees F, while in an area with hot summers, the same plant may easily be hardy to 0 degrees F. Heat hardiness is an issue that has been discussed recently, and while it is critical to those of us in warmer zones, the AHS Heat Zone map is a laughable excuse for a solution. Their heat zones are based only on the number of days above 86 degrees F. The heat map does not integrate data for humidity, or the variance between day and night temperatures which is far more important in determining how far south a plant will grow. We have continued to use the second number from the USDA map as our heat indicator number. Also related to hardiness is the issue of fertilizers. Research has indicated that a fall application of a high potassium fertilizer (assuming the plants or soils are deficient) aids in winter survivability of many plants. Conversely, an early fall application of nitrogen can make plants which are not induced into dormancy by day length, continue to grow, causing them to be more susceptible to winter damage. If you enjoy growing plants in zones which are too cold, try to create microclimates. Microclimates are areas of your garden that are particularly protected, such as near a brick wall, near heat vents from the house, near a body of water, between two structures, in courtyards, or other such areas. Good plant nuts can usually squeeze out an extra zone in either direction... that should build some egos! As mentioned, the siting of marginal plants is critical. Marginal evergreens should be located on the north side of a structure or in some shade in the winter time. With the ground frozen, the evergreen foliage is desiccated since water given off to the sun and wind cannot be replenished. With deciduous marginal plants, a location in a sunny spot will allow the ground to warm, often making the difference in survivability. Not to be overlooked are rodents that are active in the winter. Many reports of plants that didn't survive the winter temperatures, are actually plants that have become dinner to hungry rodents. Be aware particularly of voles, tiny rodents that tunnel around your plants (especially the expensive ones), and snack during the fall, winter, and spring. A dead plant with a quarter-sized tunnel nearby is a sure sign of voles. Check with your local extension service on eradication methods available in your area. Contact us to share information about performance of marginal plants in your zone. Our phone number is (919) 772-4794, our fax number is (919) 662-0370, and our E-mail address is office@plantdelights.com, or write to us at 9241 Sauls Road, Raleigh NC, 27603.

| |

|